A Photographic Folk Art of the Golden Age

March/April 2013. Vol. 4, No. 2

By George C. Gibbs

As most real-photo postcard collectors know, searching through boxes of mundane portraiture and nondescript outdoor scenes at postcard shows can be an intensely unrewarding experience. That is unless one is fortunate enough to be among the very first to flip through a box of sharp, clear images; popular topics such as trains will have chugged out of sight long before.

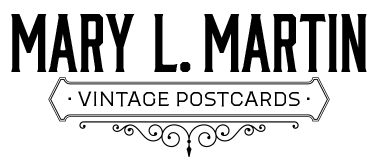

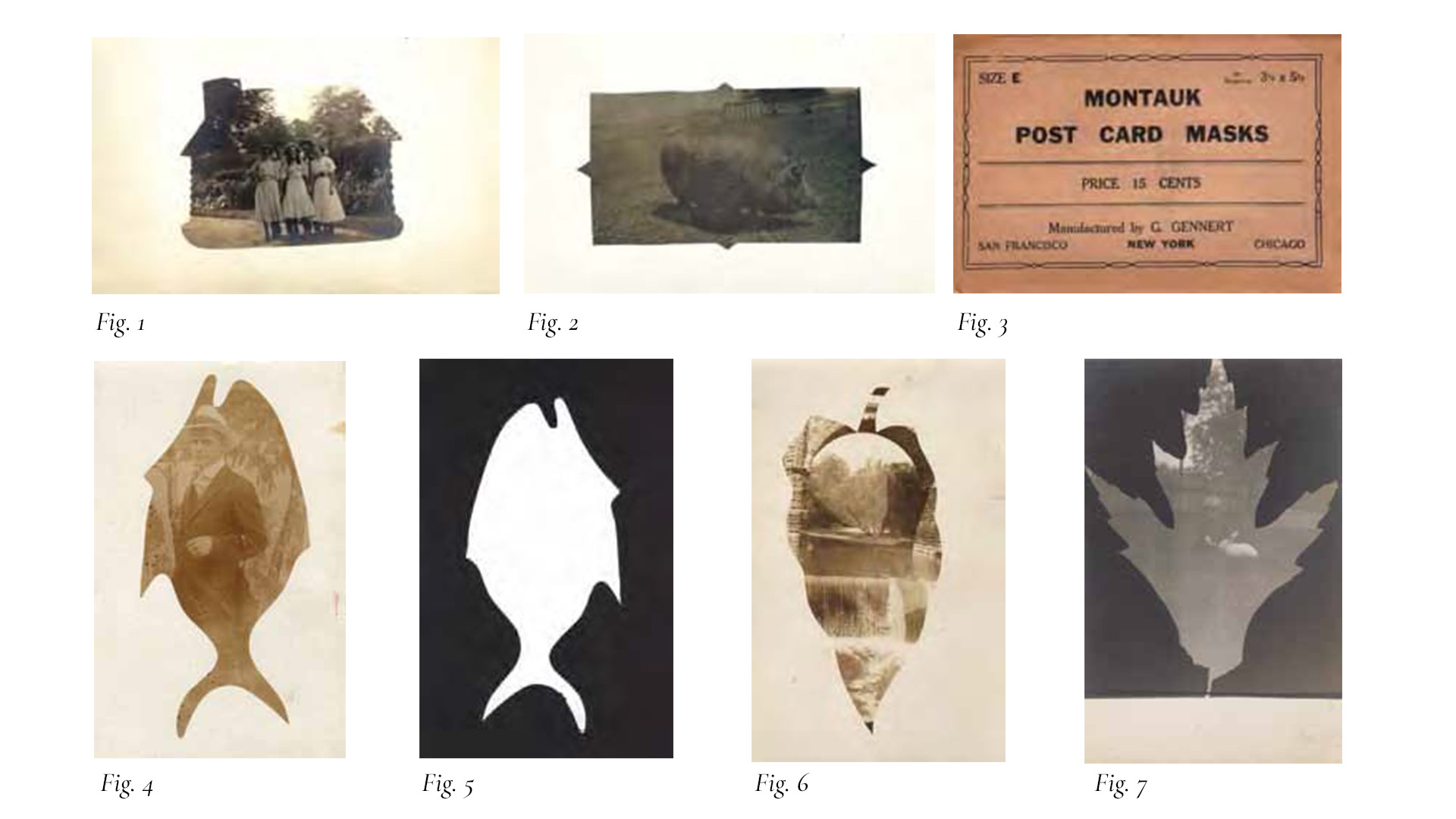

What is the collector of average means and an above-average “eye” for photography to do? Despair not, for even amongst these commonplace images are sometimes buried certain varieties that, when assembled in a small group, can make a satisfying collection, often at moderate expense. Such are the possibilities of “border” cards – real-photos wherein a white border surrounds the image so that the printed portion is in the shape of a circle, an oval, a heart, or something exotic, such as a log cabin (fig. 1). Poor cousins of the more highly regarded exaggerations and manipulated photo, border cards need not be collected with an eye towards the subject matter or quality of the image – just toward assembling as many different shapes as possible. Consider for a moment this real-photo of a pig (fig. 2). While most connoisseurs of pig postcards would turn up their snouts at such a dark image, the border aficionado could care less about pig- Real-Photo Border Cards: A Photographic Folk Art of the Golden Age By George C. Gibbs mentation and might squeal with delight upon finding what is evidently the result of using a homemade mask.

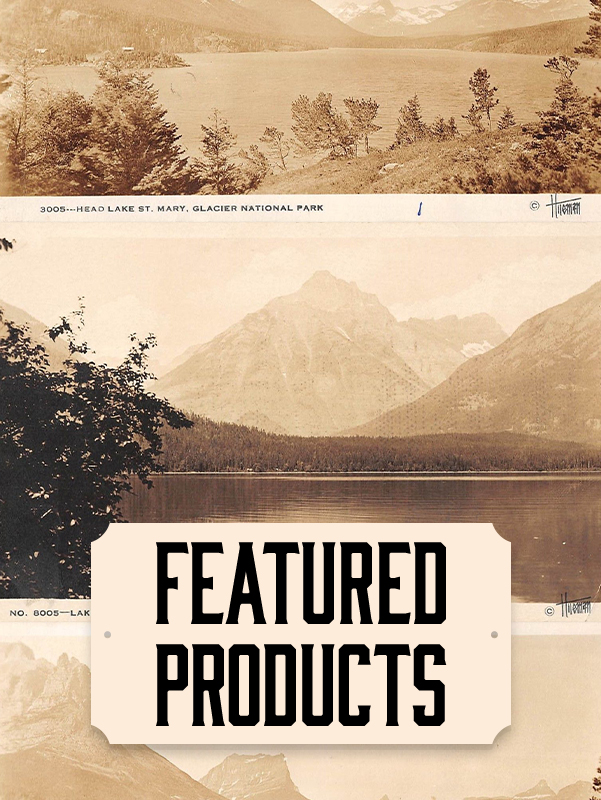

My interest in real-photo border cards was sparked many years ago during a visit to Sequoia National Park. I stumbled upon – in an antique shop, not amongst the trees –several packets, all brown and crumbly and seemingly worthless. Upon close examination however, they turned out to be “Post Card Masks” from several different manufacturers, only one of which (Ingento) did I associate with RP postcard paper (see fig. 3). Here were the names Montauk, Manning, and Housh, but where were Kodak and Ansco? Perhaps they exist, perhaps such a small market item was below their notice and they don’t exist – I’ve never found any more.

Inside these packets were designs, simple and complex, cut out from within pieces of mostly 3 ¾ x 6-inch black paper. One might guess that this fish border card (fig. 4) was the work of an imaginative amateur wielding a mean pair of scissors; this mass-produced mask (fig. 5) proves it not so. Since that day, some 20 odd years ago, I’ve reeled in about a dozen nice fish borders. Not a full creel considering that vast numbers of real photos that have swum before my eyes, so any good example is a prize catch. After all, shouldn’t a card that subtly hints the man in the portrait as a cold fish be rather scarce?

Uncanny visual effects are one of the dividends due the seeker of border cards. As Manning’s Masks advertised on its cover, “With these masks it is possible to produce better results on finished work than could be obtained without them. Poor negatives may be made to produce good pictures, which otherwise would appear flat and without contrast.” On the card in fig. 6, an unremarkable view of a bridge and waterfall is transformed into an almost abstract design through careful positioning under one of the masks in the Housh set. Note that the photographer has deftly maneuvered the negative to create dark areas at the tip of the leaf and top of the stem, while not allowing the light circle under the bridge to intrude beyond the edge of the leaf. In this way he maintains the integrity of the shape of the leaf fully, leaving no question in the mind of the viewer as to its complete contour.

Fig. 8

Not all border cards were produced with masks. When one finds a view within a black border, it was commonly created by placing a flat object on the unexposed paper –such as, in fig. 7, an actual leaf – exposing it in the darkroom, and then removing the object and printing the negative within its contours. The white border at top and bottom may be the consequence of first placing the paper in a printing frame. Once again, a mediocre negative, so poor in contrast that the child and his bunny seem to have faded into the mists of time, has grown into an image with great popular appeal (or is that oak?).

Fig. 9

Another type of real-photo merits discussion here because it, too, was produced with the aid of postcard masks. The dourfaced man in this example (fig. 8), who is pulling off the neat trick of both waving his hat and wearing it, was no doubt suffering a hangover from drinking all that Champagne! From the instructions included with a set of “Ingento Comic Masks,” one learns how this was done: “Place the comic mask in the frame over a piece of plain glass and make from it a good, strong print. Then select one of your negatives, either a single portrait or one of a group, and mask out the particular head desired, using opaque, applied on the glass side of the negative. Adjust the cut-out (a second mask with just a cut-out hole in it), which is numbered to correspond to the comic subject, over the negative so that the head will appear in the correct position and carry the printing to a good toning density.” If all this sounds rather difficult to follow and do well, it apparently was: the scarcity of decent examples is no laughing matter.

Fig. 10

The crème de la crème of real-photo border cards are the homemade types. Not only are they unique, but their creativity knows no bounds. The frogs leap to new heights, the arrows strike out in all directions, the stars throw light upon other worlds, and the boxing gloves land knockout punches. Not having seen the mask or another copy of a card with the border show in fig. 9, we can only speculate that it is homemade as it is so carefully is it cut.

It is a paradox that while a boring, low-contrast negative can yield a great border card, a perfectly exposed negative of an immensely interesting subject, such as a photographer’s wagon, may turn out to be a flop. Somehow, even if printed with a sharp eye and a deft hand, the extra element of historical content distracts from the impact of the mask itself. Usually the rule is the simpler the better.

Real-photo border cards are, in their best incarnation, a true folk art that married message with form. In fig. 10, a victorious Vermont basketball team, about 100 years ago, posed within a homemade “V” border, leaving us no doubt who won. With a little luck and perseverance, anyone can declare victory over the next ‘boring’ box of real-photo postcards they dig through.